THE NEXT 10 YEARS WILL SHAPE THE SURVIVAL OF THE NEXT GENERATION.

This isn’t an abstract theory, this is what environmental leaders are shouting. It has been echoing in my head for the past year and might have been the impetus for this life change.

Some of you may know my story, but I’d like to share how I got here...

Throughout my career, I have worked in nimble organizations with open systems and nonhierarchical expectations of self-management. We focused on process, health, relationship, rest, and sustainable growth. Lessons in my career have shown me a path from an extractive economy to a society based on principles of care, repair, imagination, and regeneration.

My career began with a decade in the hospitality industry, working with chefs committed to creating value along the entirety of the food supply chain - from seed to farmer to kitchen to consumer to decomposition. Over seven years I gained direct experience in food systems and observed the challenges that small-scale farmers and business owners face when competing with industrial procurement and distribution channels. Bio-regional foodways protect the diversity and integrity of our living ecosystems. In comparison, the Industrial Food Complex profits from the exploitation of labor and a concentration of purchasing power, a direct lineage of an agricultural system architected on the premise of labor through enslavement and the obtainment of land through genocide.

In 2016 I made a naive decision rooted in fear for our global climate crisis. Convinced of the notion that to preserve natural resources and feed a growing population we needed to manufacture food, I accepted a management position with a start-up working in Controlled Environment Agriculture. The demands of this organization were dogmatic of neo-liberal ideals, creating a working environment that led to high employee turnover. I humbly chose to walk away after I experienced a stress-induced panic attack; I had overworked and depleted my entire body’s resources. This extractive mentality of growth at the expense of health became my lesson to unlearn.

In 2017 began to shift my focus towards systems of regeneration that draw from our most beautifully efficient technology: nature. I joined the founder of L.A. Compost as his second employee and we grew the organization to a team of 12 people, managing 30 community sites, hosting over 60 annual workshops, and securing community partnerships with city municipalities, including the LA Green New Deal and Naomi Klien’s The Leap.

The organization’s overarching mission is to restore lost connections to the soil and one another. We grew our team on a sentiment of authentic relationships and slow, thoughtful growth. We incubated compost hubs across L.A. parks, gardens and recreation centers. Compost is a dynamic process of decomposition, a passage from death to life. We viewed the process of composting with more value than the quantitative impact of food waste diversion, which was significant (the equivalent of removing 90 cars from transit, annually). Our focus was on the quality of care for our team and their communities. We cultivated a company dynamic of autonomy and agency where regional managers could curate logistics in ways that suited their community while tethering to a network of support through collaboration and resource sharing. This decentralized model of operating is an essential part of the success of an organization created to serve a diverse population such as Los Angeles County. As the team grew, so did my interest in organizational dynamics.

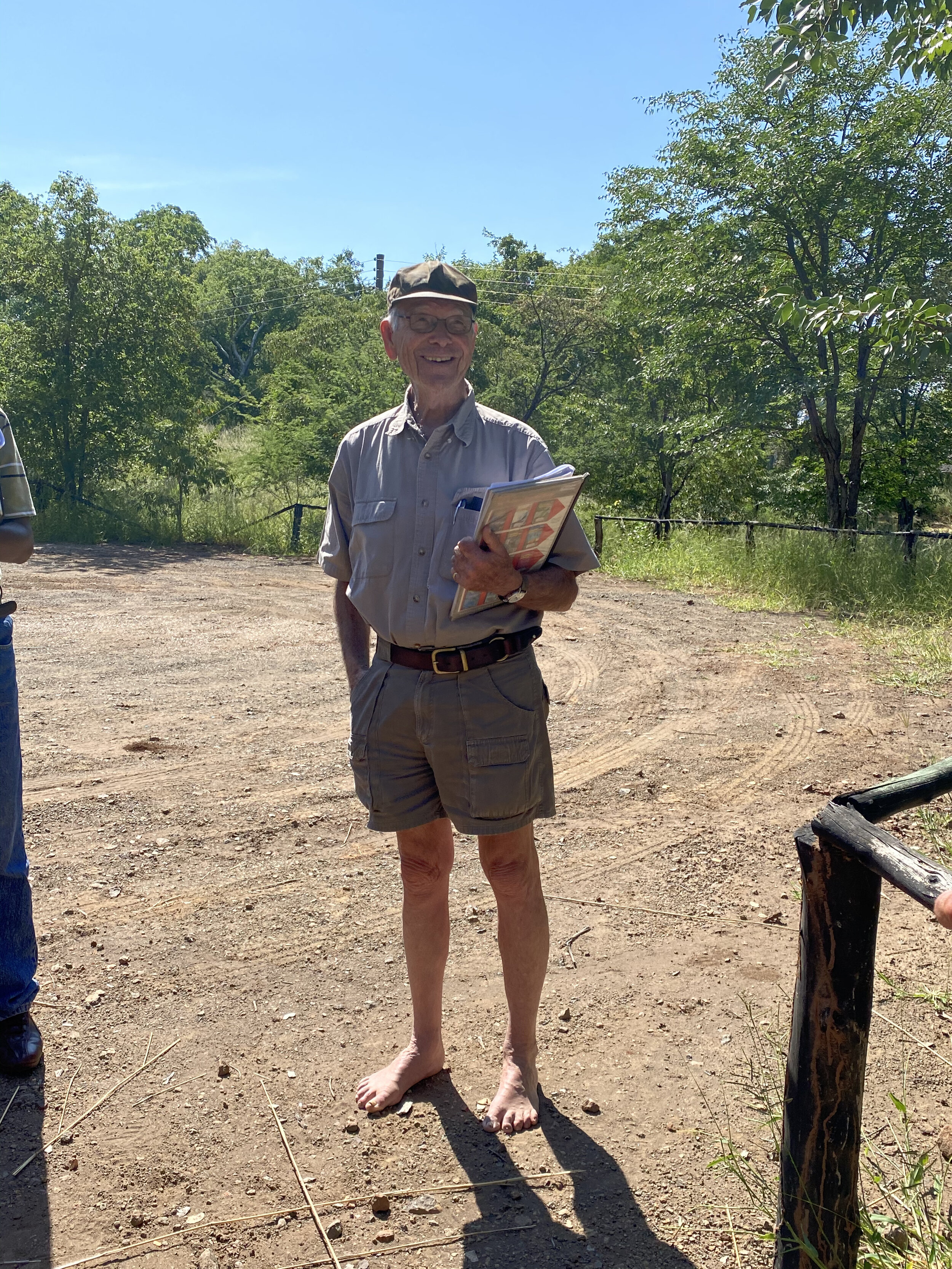

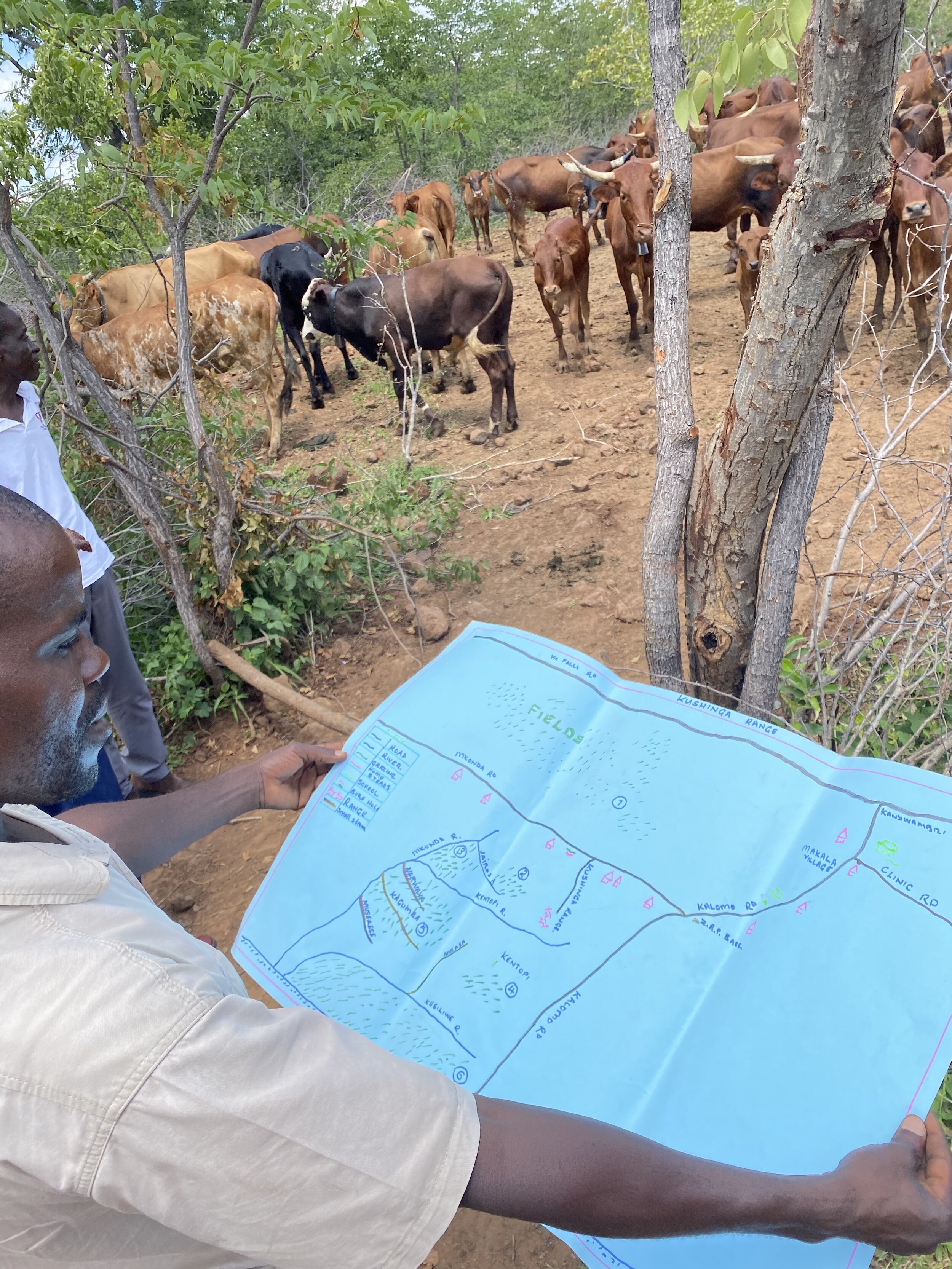

In 2019 I participated in a Regenerative Organizational Design course. This method focuses on principles of Holistic Management that center the health of an ecosystem as the measure of success, and deeply considers the context of each element within the system. The node of origin for this practice emerged from the Africa Center for Holistic Management in Dimbangombe, Zimbabwe. Coincidentally perhaps, I grew up in Zimbabwe, leaving the country in 1997 during the edge of economic collapse. After 20 years, I returned to Zimbabwe to gain hands-on experience with herders managing cattle to restore biodiversity and the local watershed. We trained over 50 herders from the surrounding regions who were encouraged to collectively plan and graze their cattle. After speaking to several groups who have been managing livestock in this way, I learned of the social benefits of these practices, mainly an increase in safety, reduction of conflict, and reconnection of community.

However, within ACHM I observed the remnants of colonialism that overshadowed the structures of management for the staff. Through meaningful friendships and conversations, I observed ingrained expectations of colonial ideals and the dis-ease it caused. I sat with the question: how can a system practicing holistic management be blind to aspects of the whole?

This led me to join a community of practice with Collective Transitions, an organization grounded on a set of transformational approaches for groups to better navigate complex societal dynamics. One approach is Systemic Constellation Mapping, with origins in Zulu familial and tribal conflict resolution. Systemic Constellation is a process of engagement to reveal, or uncover a system’s hidden patterns by inviting and reflecting on sensory information. I continue to explore this work through participatory Action Research Cohorts with a community of organizations at the forefront of advocacy and societal change.

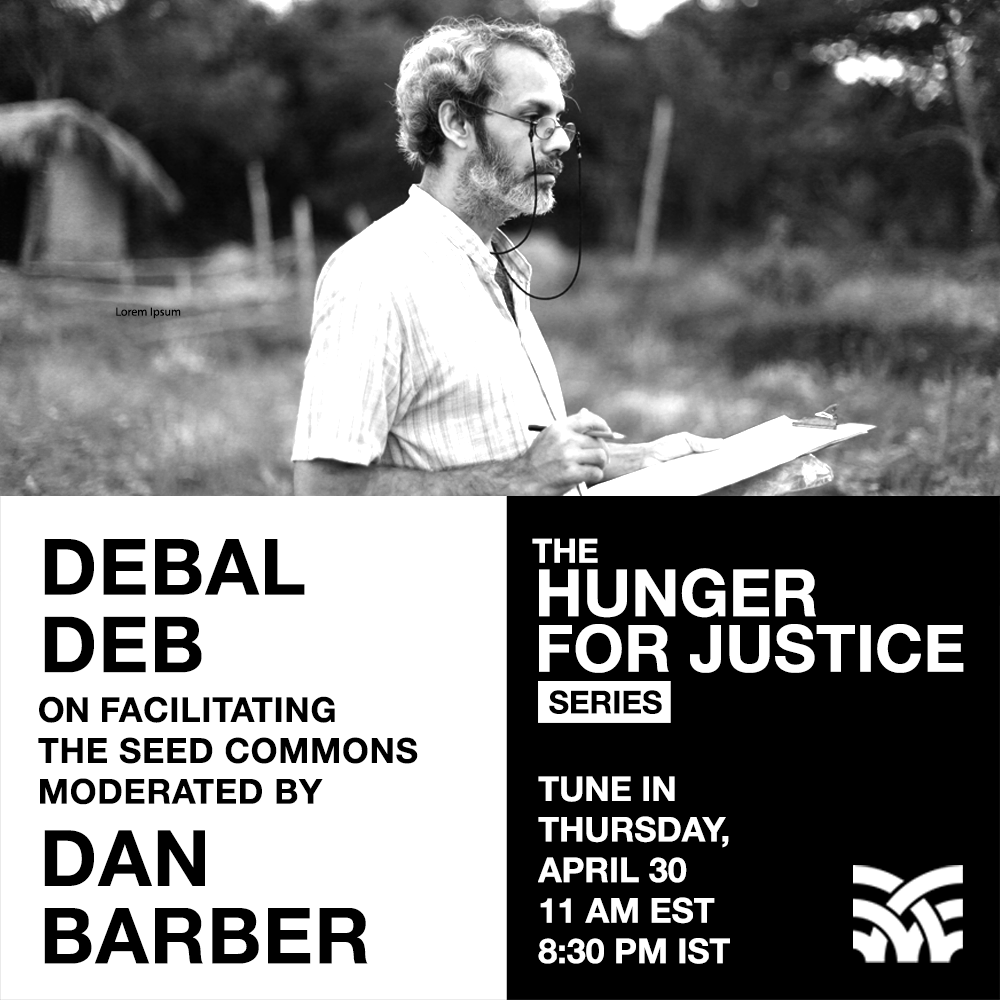

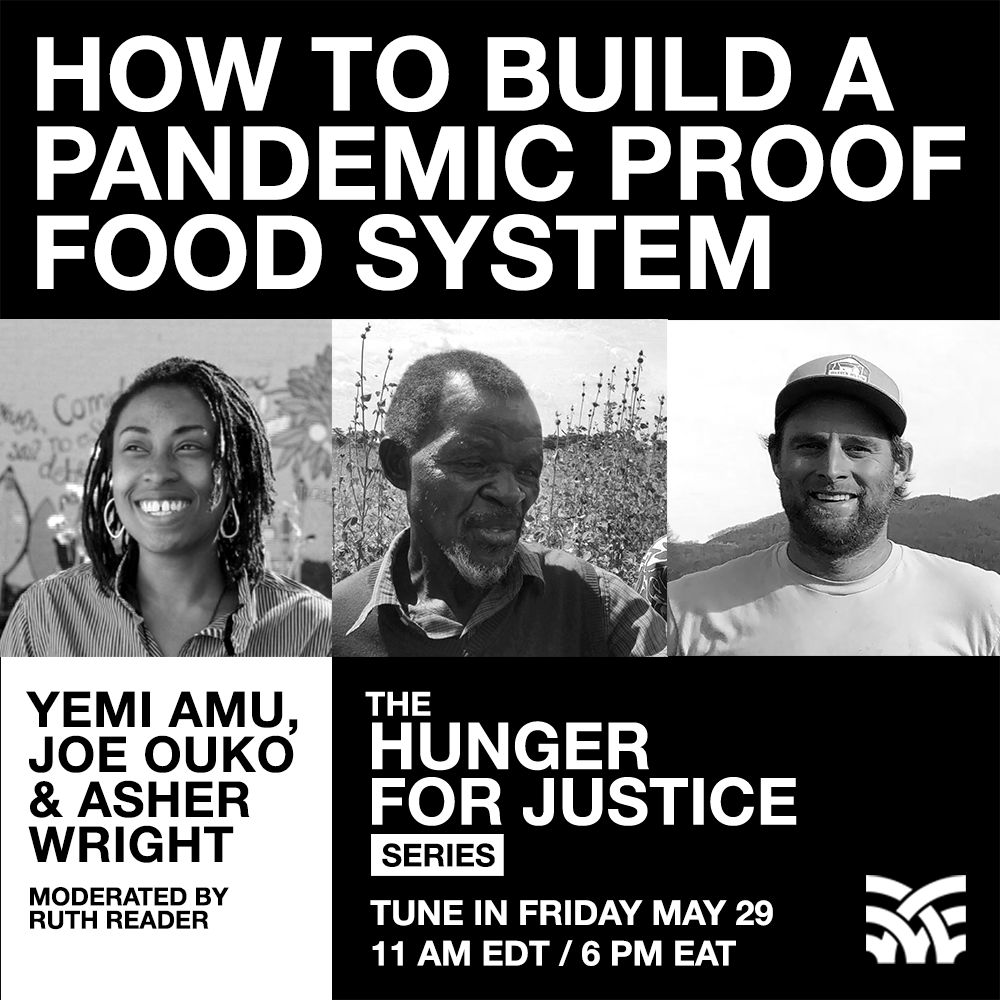

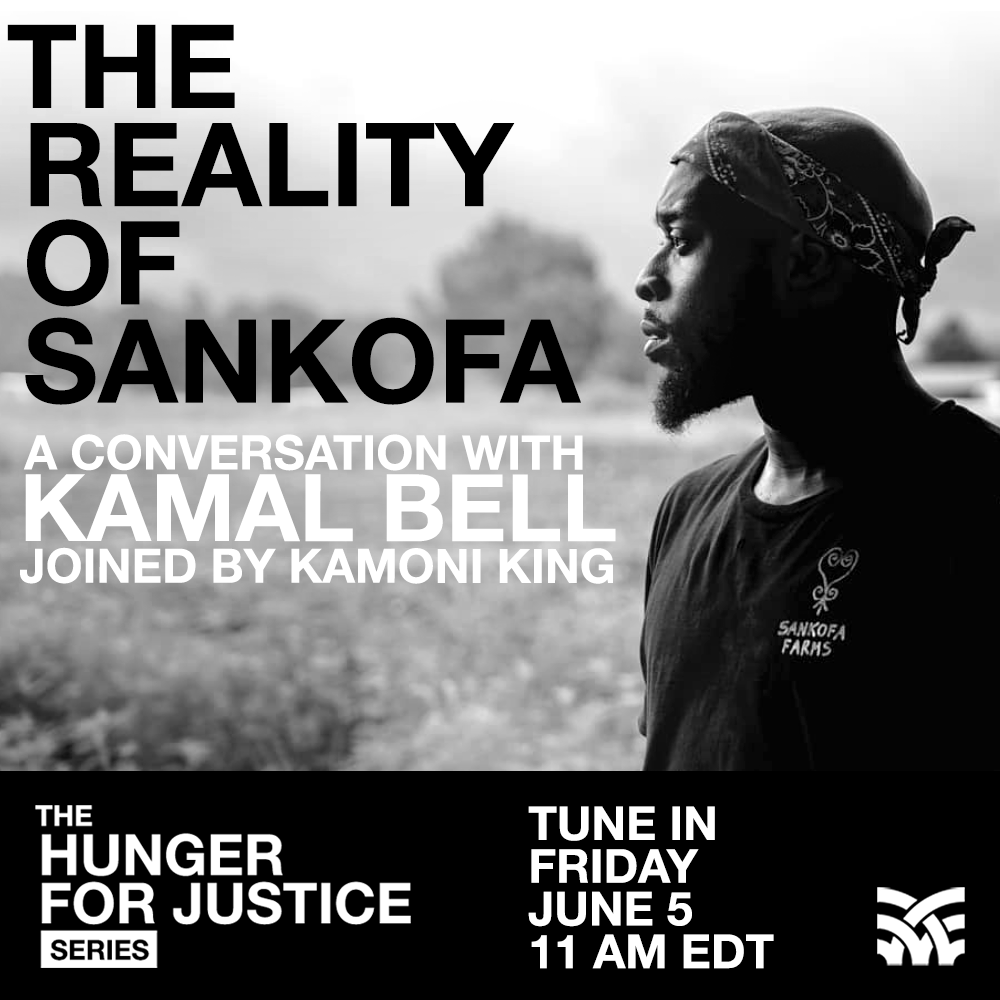

During the summer of 2020, I co-created and produced Hunger for Justice with a global NGO A Growing Culture, a YouTube series advocating for food sovereignty for small-holder farmers and the peasant food web. We facilitated the first virtual Global Farmer Innovation Fair with Prolinnova, led by farmers, hosting local farmers from Nepal, Kenya, India, Burkina Faso, and more.

My personal mission is to collaborate with individuals and organizations in a way that is restorative, joyous, and generous in the face of a paradigm shift. I invite you to join me on this emerging path.

2020

In 2010 I read Storms of My Grandchildren. Climate change felt existential and Obama was in the White House. I was working at Blue Hill at Stone Barns and brewing a cauldron of optimism, abundance, and joy for the future. I was focused on my desire for delicious food, with budding curiosities for how food is grown, prepared and served. I learned a lot, but there was a growing fear because storms were coming. I learned more about inequalities in food distribution, I learned that there are only 50 years of harvestable topsoil on our planet, and I could feel the threat of an unstable climate. I made a decision rooted in fear and took a job working in Controlled Environment Agriculture. I worked in a blue-lit shipping container for 10 hours a day, with an isle the width of just my body. I adopted the notion that to feed a growing population we need to manufacture food.

The spell I was under broke through a series of events, starting with a moment of panic that flooded my body to the point where I lost feeling in my limbs. My jaw and my face tightened, my hands became numb claws, and a kind stranger, on the side of the road, on the way to a job interview had to call for help. I had overworked and depleted my entire body’s resources. This extractive mentality of growth at the expense of health became my lesson to unlearn.

And then I found the church of compost.

I joke about this because connecting to nature has a spiritual resonance. Yes, I learned that healthy soils are proven to increase serotonin, decrease stress and improve cognitive function, but I also experienced a belonging, in my body, when I was in my work boots in the sun turning a hot compost pile. I was engulfed with curiosity about the soil food web, mycelium, and the dynamics of nature’s cycles. I learned that regenerative stewardship of the land, with goals to improve the health of the system, result in carbon drawdown. Better yet, this practice of holistic management can increase the overall carrying capacity of the ecosystem - literally unlocking potential.

My mission for the next few months is to explore regenerative tools for resilient and adaptive growth. I am starting with Holistic Land Management at the Dimbangombe Lodge in Zimbabwe and will be connecting with others along the way.

If you would like to contribute to my journey you can donate here.

“We are all alive at the last possible moment when changing course can mean saving lives on a truly unimaginable scale.” - Naomi Klein

I’m somewhat surprised that two weeks have passed. Some days are filled with long activities, hours in the sun and bush drives through the most rural parts of Zimbabwe. Other days I spend watching the rain and going to sleep as soon as the sun goes down. I’m learning about the Tonga, Ndebele and Nambia peoples from Matabeleland. I’m writing down phrases as I’m learning Ndebele and spell check doesn’t recognize any of the words so I’m constantly having to rewrite entire phrases after the phone auto corrects. Auto-correct is becoming irrelevant. I’m understanding the language of our world through the lens of the people I meet.

I’ve been curious as to why Holistic Management hasn’t been more widely adopted by the surrounding communities. It clearly yields more crop and builds up grasslands, and ACHM has initiated training on how to organize and implement the practice. To get individuals in a community to bring their livestock (aka their livelihood) together first requires trust. It's like saying we’re all going to collectively put money into the pot and pass around the pot sharing the responsibility and protecting our investments (literally from predators). With collective herding the benefits are compounding with time, creating long term stability of the land (aka livelihood). The benefits are also social. Some of the women that I met explained that what has changed is there used to be a lot of anger between neighbors, becoming suspicious if a cow went missing and resentful if the same low rainfall produced more on another's fields. The women said that herding together has brought them together, their cattle are safer, they have more time to spend on other duties, and they are making decisions as a community. The biggest challenges seem to be that managing together requires ongoing communication and problem solving, and keeping motivation to work together requires leadership that believes in the long term results. I can understand why that kind of leadership can be questioned when more immediate needs aren’t consistently met.

In a nutshell - planning financial and land management based on a holistic context determined by individuals involved in the whole, and their environment. A key component is cattle grazing so that land can regenerate, allowing for rest periods instead of consistently grazing the same plot of land until it's bare, this allows for restoration of grasslands over larger amounts of land, which is essential for the livelihoods of the people and the planet.

Holistic Management as an agricultural practice is simply a return to how many of these communities first farmed. This strategy works alongside wildlife instead of sectioning off areas for individual human use. However the communal way of organizing is more than a generation’s history and communities here no longer farm in this way - each household has their own cattle and crop, fenced up, sizing up their neighbor’s harvest.

The first step to Holistic Management is to define what makes sense in a holistic context. To define a holistic context, an individual or group defines (aka imagines up) and agrees upon a quality of life that includes desires and beliefs of the group and its environment. It is never a plug and play model, it is inherently dependent on the individuals participating and the conditions of their environment. It requires an acknowledgement of a collective, community culture. It is a process, a practice, a vision that shifts and evolves as the group consciousness grows.

I met Chido Govera (her story from MAD conference 2012) at her homestead about 30km outside Harare. Like many people here who are coping with frequent power cuts, her and her family (she is a mother of 5 orphaned daughters), have installed solar power for water and electricity. She grows red corn, sweet corn, black corn, pumpkins, sweet potatoes, onions, long beans, green beans, coffee, turmeric, teas, herbs and more...she is replanting a segment of her property to increase garlic production for export. For meat they raise rabbits and chickens, she's planning for goats soon (to help cut back grasses that attract snakes) and is curious about making cheese. Her main focus is mushrooms. She is building a lab to safely sell mushroom spawn. And she already has contracts with market retailers. She is doing all of this on less than 2 hectares of land.

Zimbabwe's history around land is tumultuous and not the topic of this email (otherwise it would be a few more pages). wiki page here. Chido doesn't depend on supermarkets and municipalities, she is redefining the narrative of what land management can look like for Zimbabweans.

It can be challenging to understand another person's context, yet in the context of humans we need healthy food, clean water, compassion as we grow, encouragement from others, time to be understood, and a sense of value and purpose.

A few weeks later, Covid-19 shocked the globe.

Upon request from my family, and the US Embassy, I returned to America. This crisis not only exposed our global vulnerability from a health perspective, it exposed inequality in a way that could no longer be ignored by the mainstream.

I adapted quickly and launched a new project.

#HungerforJustice.